Retrofit of Heritage Buildings

Getting the details right at New Court, Cambridge

I recently attended a short presentation by Oliver Smith and Joel Gustafsson on New Court, Cambridge. Oliver works at 5th Studio and Joel now has his own consulting firm JGC, although his work on this project was for Max Fordham.

They explained their approach to the dilemma of what to do with a 200 year old Grade I listed building, in poor condition, and that’s not fit for purpose.

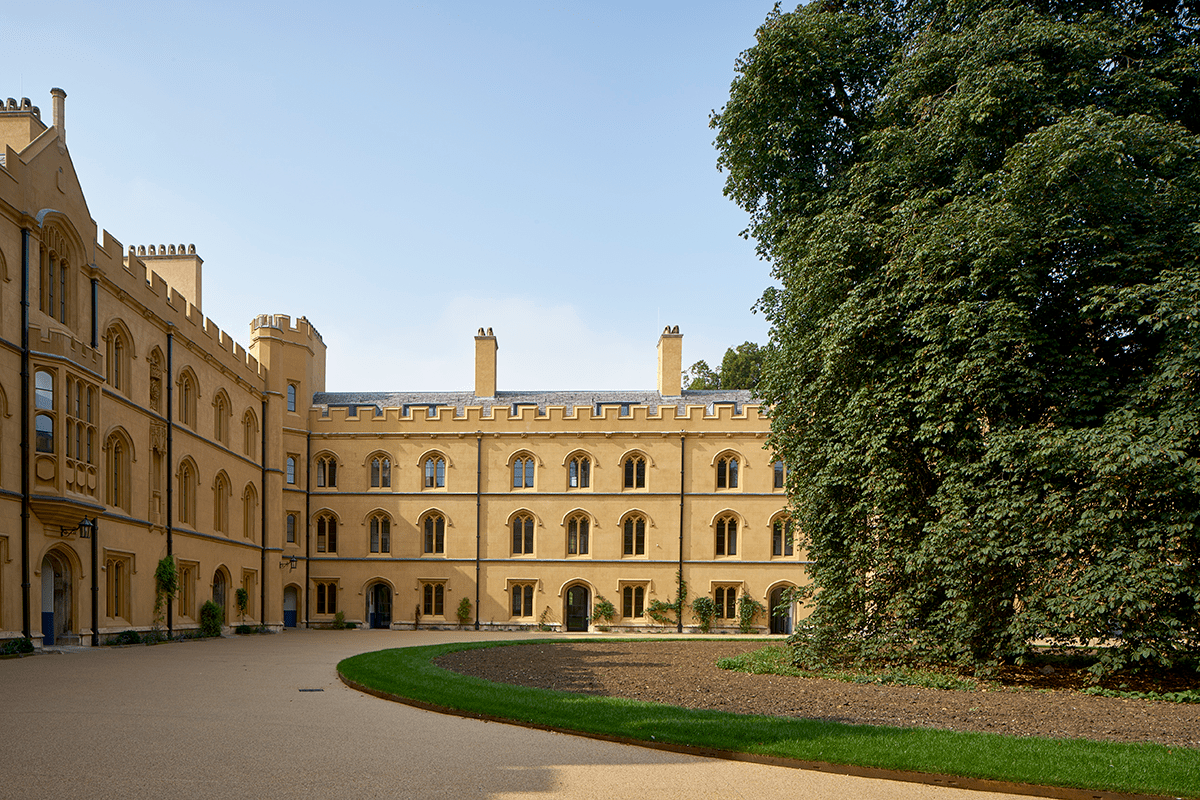

New Court is a four-storey, neo-Gothic building which contained student study bedrooms, offices and teaching spaces arranged around a central court. The refurbishment took place a few years ago and comprised extensive refurbishment of the interior spaces, with new service installations and renewed facades.

The brief was to create 21st Century accommodation for Trinity College, which was explained to mean 1) vastly reduced energy costs; 2) retention of character and heritage; and 3) not taking forever and getting stuck in a ‘going nowhere’ listed building application.

The team had apparently considered knock down and rebuild, however it was the ‘not getting stuck’ in the planning process that quickly led them to develop ideas around a refurbishment. The University Estate’s expansive portfolio of listed buildings meant this project’s brief quickly expanded to setting standards and methods for future retrofit projects - given the lacking precedent for converting Grade I listed buildings with such ambitious (Passivhaus) energy targets, an example of how to do this well was sorely needed.

As might be expected, detailed questions from the clever folk at Cambridge (who even established a technical committee to scrutinise things) translated to pretty detailed analysis, but cutting through the vast array of charts they showed, I took away some simple conclusions whilst also busting some myths.

MYTH: you can’t insulate solid walls on the inside - you can, as they have proven by detailed analysis. They explained how each elevation and wall thickness was modelled to find the exact insulation thickness. Then they did the builders a favour by rationalising this to a standard thickness, but not without checking the risk areas where they might have been over or under insulating.

DO: modelling - take samples, analyse the existing condition, model carefully and even do a mock-up to validate.

MYTH: Cold bridges occur at return walls - through their modelling, they showed that of course you do get cooler areas (“cool bridges”), but not something that would present a problem. This modelling justified the omission of awkward and unsightly extensions of wall insulation on return walls.

DON’T: over insulate - instead balance energy loss across the envelope (walls, roof, windows) with electrified heating and heat recovery. Use those models to help find the balance.

MYTH: you can’t do MVHR in listed interiors - whilst it was clearly a challenge, they managed to do it successfully.

MYTH: you can’t fit double glazing into historic window frames - apparently they challenged the planning officers to find a sample DGU within an array of windows and they failed - that’s what I call a pre-app!

MYTH: you can’t install underfloor heating below existing floor boards - ironically they said the existing boards were far more stable that more recent replacements.

Balancing Solutions

The analysis presented was heavily focused on energy loss and how to deal with the thick (and sometimes poorly constructed) walls - it was explained how crucial this is to avoid interstitial condensation within the wall which can cause problematic mold in the wall itself and even present as damp on the inside face.

The key is to understand the temperature and dew point gradients in the wall and ensure they don’t touch or cross. Having studied the existing wall using surveys and measurements throughout the depth, they found the wall’s existing condition was quite stable in this regard, and so their challenge was actually to not over-insulate the walls on the inside, which would change the temperature gradient too much. They did this using the WUFI modelling tool.

But this obviously works against the desire to insulate the building to limit energy loss. That’s where we heard about their other important moves.

First was to avoid vapour barriers and phenolic foam, instead opting for wood fibre insulation board and no vapour barrier. This better allowed moisture to move through the wall, reducing any risk of build-up and thus better reflecting the existing condition.

Second was to assess the windows (a weak point in energy loss terms), and they found a Holloseal solution where fitting a DGU into the existing frames could be agreeable and practical.

Third was to introduce an MVHR system which was an extremely tight fit to shoehorn all the kit and pipes into the limited space.

Oliver explained how their approach to building fabric and MEP design was hand-in-glove, as these things together make up a ‘whole system’ and solutions should not be developed in isolation. He noted how in recent decades heating systems and built fabric works had been undertaken in isolation, often solving one issue and creating another.

Although we didn’t have time to hear the detail, there was clearly a lot of thought that went into the interior fit-out, for example how the partitions and finishes were deliberately set back or below the retained cornice.